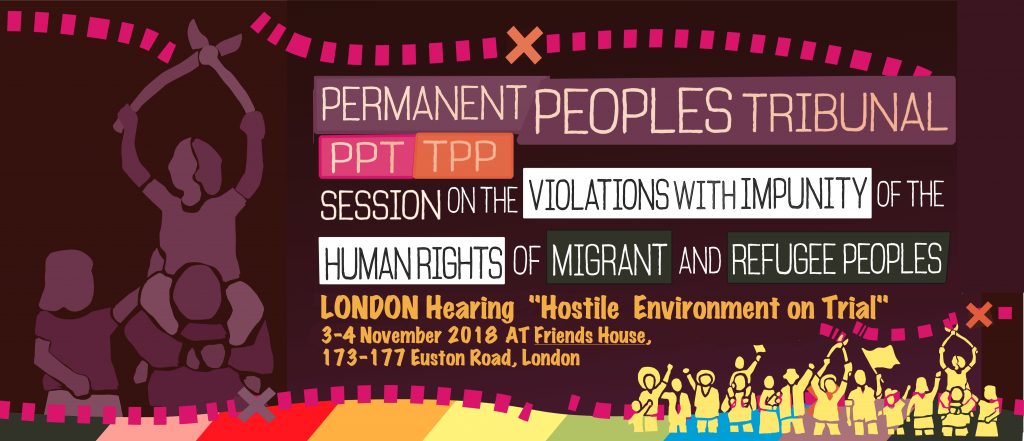

INDICTMENT London Hearing 2018

October 2018

This indictment is also available on PDF, please click here for English, click here for Spanish

The Defendant to this indictment is the British government (in its own right and as representative of the governments of the EU and of the global North).

1. Preamble

This session calls on the Permanent Peoples’ Tribunal to consider whether the policies of theEuropean Union and its member states in the field of immigration and asylum, particularly as they affect migrant peoples in the chain of labour, amount to serious violations of the articles enshrined in the Universal Declaration of the Rights of Peoples signed in Algiers on 4 July 1976, to serious violations of the rights of individuals as enshrined in particular in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights 1948, and, in their totality, to a crime against humanity within the meaning of Art. 7 of the Rome Statute.

The current indictment is presented as one of a series of indictments against the governments of the global North within the framework set out at the introductory hearing in Barcelona in July 2017. These indictments taken together set out the ways in which the governments of the global North and the institutions of the EU have (a) created conditions making life unsustainable for millions in the global South, thus causing mass forced migration; (b) treated those migrating to the global North as non-persons, by denying them the rights owed to all humans by virtue of their common humanity, including rights to life, dignity and freedom; (c) created zones which are in practice excluded from the rule of law and human rights within the global North.

Governments of the global North, together with the international financial institutions, pursue trade, investment, financial, foreign relations, and development policies which uphold a system of global exploitation that destabilises governments, causes armed conflict, degrades the environment and impoverishes and immiserate workers and communities in the global South, thereby forcing millions to leave their homes to seek safety, security and livelihood elsewhere.

At the same time, through policies of deregulation, privatisation, welfare state retrenchment and outsourcing of government functions, marketisation and flexibilisation, the restructuring of work and labour relations have been enabled in the global North, creating acute insecurity and precarity, depressing real wages and conditions of work for most workers.

Through labour and migration policies which permit freedom of movement for capital and for citizens of the global North while denying such freedoms to the citizens of the global South, their governments have allowed employers to take advantage of the vulnerability of migrants and refugees as they attempt to enter the labour market, which has created a migrant and refugee underclass of illegalised, super-exploited, deportable workers – a people without rights.

Migrants, people forced to move from the global South to the global North for reasons of war, conflict, persecution, dispossession and poverty, suffer violations of rights with impunity when they reach the global North regardless of their particular nationality or ethnicity. By virtue of their common experience they can be said to constitute a ‘people’ for the purposes of the Universal Declaration of the Rights of Peoples (the Algiers Declaration), which provides that every people has a right to existence, and that no one shall be subjected, because of his national or cultural identity, to … persecution, deportation, expulsion or living conditions such as may compromise the identity or integrity of the people to which s/he belongs.

The following sub-articles of Art. 7 of the Rome Statute (crimes against humanity) are relevant to the considerations of the Tribunal: c) Enslavement; d) Forced deportation or transfer of the population; e) Imprisonment and other serious forms of denial of personal freedom in violation of fundamental norms of international law; g) Rape, sexual slavery, forced prostitution … and other forms of sexual violence of equal seriousness; h) Persecution against a group or a collective possessing their own identity, inspired by reasons of a political, racial, national, ethnic, cultural, religious or gender-based nature; i) Forced disappearances of people; j) Apartheid; k) Other inhuman acts of the same nature aimed at intentionally causing great suffering or serious prejudice to the physical integrity or to physical or mental health.

Other relevant human rights instruments engaged by the indictment include: The Universal Declaration on Human Rights (1948); The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (1966), the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (1966), the Convention for the Suppression of the Traffic in Persons and of the Exploitation of the Prostitution of Others, the Protocol to Punish Trafficking in Persons, especially Women and Children; the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment; the Convention on the Elimination of all forms of Racial Discrimination; the Convention on the Elimination of all forms of Discrimination against Women; the Convention on the Rights of the Child; the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights (2000); the ILO Migration for Employment Convention (Revised) (1949), all of which have been ratified by EU member states.

Within this framework, the current indictment asks the Permanent Peoples’ Tribunal to consider the economic, security, migration and labour policies of the EU and its member states, which together exclude, marginalise and deny basic human rights to poor migrants and refugees both at the borders and within Europe. In the UK, these policies are collectively known as the ‘hostile environment’, policies which have the avowed aim of making life impossible for migrants and refugees who do not have permission to live in the UK, and which remove such migrants from the rights to housing, health, livelihood and a decent standard of living, liberty, freedom of assembly and association, family and private life, physical and moral integrity, freedom from inhuman or degrading treatment, and in the final analysis the right to human dignity and to life. The Tribunal will also be requested to examine the legal infrastructure which underlies the ‘hostile environment’, in which migrants and refugees, with or without permission to be in the country, are in practice possessed of no rights, but at best privileges which can be withdrawn at any time.

While the ‘hostile environment’ policies have features particular to the UK, there are parallel provisions in other EU member states, which deny undocumented migrants access to housing, health care, employment and livelihood. Such policies are paradigmatic of the EU-wide treatment of poor migrants and refugees as undesirable and undeserving of human rights. This contempt finds multiple expressions, from the criminalisation of rescue in the Mediterranean, to the maintenance of inhuman and degrading conditions at refugee camps from Moria in Greece to Calais, France. It spreads downwards from government and encourages the growth of more and more extreme anti-immigrant racism and violence.

The note below sets out some of the features of the ‘hostile environment’ for migrants developed as policy in the UK since 2012, with their historical roots.

2. Explanatory note: the ‘hostile environment’

In 2012, the UK home secretary Theresa May said that she planned to create a ‘really hostile environment’ for illegal immigrants in the UK, so they would leave the country. In the wake of her announcement, she set up an inter-ministerial ‘Hostile Environment Working Group’ (a title later changed, at the request of coalition partners in government, to ‘Inter-ministerial group on migrants’ access to benefits and public services’, tasked with devising measures which would make life as difficult as possible for undocumented migrants and their families in the UK. The explicit intention is thus to weaponise total destitution and right-lessness, so as to force migrants without the right to be in the country to deport themselves, at low or no cost to the UK.

The policies which this group devised were contained in the 2014 and 2016 Immigration Acts, in secondary legislation and guidance documents, and in operational measures adopted by the Home Office and partner agencies. They include:

(1) Housing: The ‘right to rent’requires private landlords to perform immigration checks on prospective tenants, their families and anyone else who might be living with them. Landlords renting property are liable to penalties and potentially to imprisonment if someone without permission to be in the UK is found living as a tenant or lodger in their property. The right to rent was piloted in 2014 and was extended throughout the country in 2016, despite an (unpublished) Home Office survey indicating it was not working and was leading to greater racial discrimination in the housing rental market, findings confirmed by civil society organisations and landlords’ associations (Joint Council for the Welfare of Immigrants, 2015, 2017).

Those who cannot prove their citizenship or status in the UK, and are unable to access rented property and have ended up homeless and on the streets, include a significant number of pensioners who have lived in the UK since early childhood (the ‘Windrush generation’).

Acts of parliament in 1996 and 1999 had excluded asylum seekers, undocumented migrants and migrants on temporary work visas from homeless persons’ housing and social housing tenancies (the Immigration and Asylum Act 1999 created a separate agency to provide destitute asylum seekers with no-choice accommodation outside London and the south-east).

The ‘right to rent’ measures breach the right to adequate housing without discrimination, which is recognised in the Universal Declaration on Human Rights (UDHR) Art 25 (as an integral part of the right to an adequate standard of living), and in Art 11 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), further amplified by General Comment No 4 on Adequate Housing by the UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (1991). Insofar as homelessless affects human dignity and physical and mental integrity, the measures also breach Art 1 UDHR, Arts 3 and 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) and Arts 1 and 3 of the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights (EUCFR).

(2) Health care: A requirement for National Health Service hospital staff to check the immigration status of all those attending for non-emergency treatment, and to demand full payment in advance from those unable to show their entitlement to free treatment, was implemented through regulations which came into force in April 2017. Those unable to establish their lawful status in the UK and those with visitor status are charged 150 per cent of the cost of treatment. Emergency treatment does not require advance payment but patients are invoiced later for it. The regulations followed restrictions on free hospital treatment in 2015, since when those in the UK as students or with work visas have been required to pay an annual health levy (now £400 per person per year).

They have resulted in many expectant mothers not attending for ante-natal treatment, causing lasting damage to their unborn children, and to cancer patients and others with very serious conditions being unable to start treatment for lack of funds.

The Health and Social Care Act of 2012 allowed the NHS to pass on details of patients to the Home Office for enforcement, and informal arrangements for such data sharing were replaced by a formal agreement (MoU) in January 2017. After doctors’ groups such as the British Medical Association (BMA), medical charities including Doctors of the World, campaign groups such as Docs not Cops and members of parliament in the select committee on health called on the government to end the agreement, which was deterring sick people and expectant mothers from seeking medical help, the government announced a partial suspension of the MoU in April 2018.

NHS Regulations had from 1982 onwards provided that visitors to the UK were not entitled to free non-emergency hospital treatment, although NHS staff were not obliged to charge or to perform immigration status checks and most did not. Primary health care (at doctors’ surgeries) remains free to all regardless of status, as attempts by government to extend the charging regime to primary care have met with very strong resistance from NHS and public health workers.

The denial of free hospital treatment to those in need, who cannot prove their immigration status or do not have secure status, and/ or measures which deter people from seeking medical treatment, violate the right to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health, which is one of the fundamental rights of every human being, without distinction of race, religion, political belief or social or economic condition. It is reflected in the 1946 Constitution of the World Health Organisation, in Art 25 UDHR and in Art 12 ICESCR 1966. It also violates the right to physical and mental moral integrity recognized in Art 8 ECHR and Art 3 EUCFR.

(3) Criminalising work The 2016 Immigration Act continued and perfected the process of criminalisation of migrants’ work which had started two decades before, when in 1996, the ban on work for asylum seekers and for those without permission to be in the country began to be enforced by employer sanctions: penalties for employers who employed those without authorisation to work in the UK. While the law was hardly used, it paved the way for much stricter sanctions in 2006, with the creation of a criminal (as opposed to a regulatory) offence of knowingly employing unauthorised workers, which carried a prison sentence; increased regulatory penalties; stricter documentary checks for employers to avoid penalties; and intensive enforcement through raids on mainly small, ethnic-owned workplaces. In 2016, the penalty was doubled to £20,000 per worker, and a new criminal offence of illegal working was created, which enabled undocumented workers’ wages to be confiscated.

Opportunities for legal work in the UK have been closely tailored to the demands of the economy since the post-second world war reconstruction. From the 1971 Immigration Act onwards, unskilled workers from outside the EU were not admitted, apart from groups such as seasonal agricultural workers and domestic workers - temporary workers with no rights of settlement or family unity, controlled entirely by their employers and not permitted to change employer. Asylum seekers were not permitted to work while they waited for their cases to be determined, a process which could take years. Visas for work have largely been restricted to those with a high level of education, qualification and income (and since 2009, under the points-based system, points are also awarded for youth). In 2010, graduates were no longer permitted as before to remain in the UK for two years for post-study work.

As from 2016, too, immigration rules were changed to remove rights to settlement for those earning under £35,000 per year. This measure was introduced so as to ensure that ‘only the brightest and best workers who strengthen the UK economy’ are allowed to settle permanently in the UK; the others are now required to leave the UK after six years. The rationale for the rule changes is thus unashamedly neoliberal and nativist, treating the workers concerned as disposable commodities.

At the same time, while EU nationals have rights to move freely around the EU for work, homeless EU nationals from eastern Europe found sleeping rough in London have had their identity documents confiscated, which prevents them from obtaining employment, and they have found themselves detained and deported for ‘abuse’ of free movement rights.

These measures breach the right to work recognised as universal by Art 23 UDHR, and enshrined in Art 6 ICESCR and Art 15(1) EUCFR.

They should be seen against the background in which the governments and institutions of the EU and of the global North have abdicated their international law obligations to protect workers and ensure decent working conditions and fair pay, enabling the entrenchment of exploitative labour practices and oppressive labour conditions in both the public and the private sector. In the UK, the government has repeatedly refused pay rises to public sector workers while allowing managers to take obscenely high salaries; refused to adopt a genuine living wage; failed to enforce minimum wage and other labour protection vigorously; and has encouraged or condoned companies’ use of zero-hours contracts, their manipulation of ‘self-employed’ status, agency working, undermining of the right to organise and other actions which deny rights and protections to workers and employees.

These acts and omissions breach the right to just and favourable conditions of work protected by Art 23 UDHR, and to freedom, equity, safety and security at work, contrary to the Conventions of the International Labour Organisation (ILO).[1]

(4) Social security and asylum support: Migrants admitted to the UK for visits, work, study or family reunion are subject to a condition of ‘no recourse to public funds’ which prohibits access to means-tested benefits. Since 1999, they have been disqualified by social security regulations from access to any such benefits.

Asylum seekers are eligible to receive about £37 per week (an amount which in 2014 represented around 50 percent of basic income support). The level of support was based on the assumption that the determination period would be around six months, since it was accepted that no one could live on this amount for longer. The period for determination of claims is frequently measured in years rather than months, but the amount has not risen in line with living costs. Support was denied to late and refused claimants in 1996 and again by legislation in 2002. and in 2009 the removal of basic benefits and accommodation was extended to families with children who did not leave the UK when required to. Those eligible for asylum support often have to wait for several weeks or months to obtain it, leaving many homeless and utterly destitute.

In 2007 the Joint Parliamentary Committee on Human Rights condemned the level of and exclusions from asylum support as ‘enforced destitution’, which ‘in a number of cases reaches the threshold of inhuman and degrading treatment’. It concluded that the ‘deliberate policy of destitution falls below the requirements of the common law of humanity and of international human rights law.’ A 2014 report by IRIS, Poverty among refugees and asylum seekers in the UK. An evidence and policy review, found that destitution was a deliberate policy calculated as a deterrent to others considering coming to the UK.

Measures deliberately depriving anyone of the means of life breach Arts 9 and 11 ICESCR (right to social security and to an adequate standard of living), and may also constitute inhuman and degrading treatment contrary to Art 5 UDHR, Art 3 ECHR and Art 4 EUCFR.

(5) Education: In June 2015 the Department for Education (DfE) entered an agreement with the Home Office to pass on details of school pupils obtained through the schools census, to enable the Home Office to trace unlawfully staying families for deportation. The agreement, whose aims included the creation of a ‘hostile environment’ in schools, was secret, and only came to light in December 2016, after the DfE added questions on nationality and country of birth to the census. A proposal by the home secretary not to permit children of migrants with irregular status to attend school or to push them to the back of the queue for school places, was rejected by the government. A public campaign by activist group Against Borders for Children, supported by teachers and parents, led to the dropping of the nationality and country of birth questions from the school census in April 2018, but the data sharing agreement remains in force, and campaigners believe it deters those with irregular status from sending their children to school.

Insofar as the measures are calculated to deter parents from sending children to school, they breach the universal right to education without discrimination, recognised by (inter alia) Art 26 UDHR, Arts 13 and 14 ICESCR, Protocol 1 Art 2 of the European Convention on Human Rights, (ECHR), Art 14 EUCFR and Art 28 UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC).

(6) Other data sharing measures: Apart from the measures described above in relation to the NHS and schools, the 2016 Immigration Act imposed a general duty on public bodies and others to share data and documents with the Home Office for immigration enforcement. In addition, from January 2018 banks have been obliged to conduct quarterly checks on current account holders and to close accounts of those suspected by the Home Office of unlawful stay. These provisions were suspended in May 2018.

Powers to share data with and to require the provision of information to the Home Office by other government departments and agencies, including Her Majesty’s Revenue and Customs, marriage registrars and local authorities, were granted by legislation from 1999 on.

From 2009, universities and colleges were obliged to collect and transmit to the Home Office the personal details, attendance, progress and other relevant information on non-EU students enrolled on courses, as well as to check the documents of all staff including visiting lecturers. Failure to monitor students led to suspension and in some cases withdrawal of their licence to enrol non-EU students.

The Data Protection Act 2018 exempts data collected and shared for immigration control purposes from rights of data subjects to access the data held on them, to the extent that disclosure may prejudice immigration control.

These measures disproportionately interfere with rights to privacy (Art 8 ECHR) and data protection (Art 8 EUCFR).

(7) Commercial fees: Home Office fees for visas and their renewal have risen exponentially in recent years, to reflect ‘the value of the product’, which makes applications for settlement, for regularisation or for citizenship prohibitively expensive. An application for settled status for a woman subjected to domestic violence by a spouse costs £2,997; for a dependent relative it now costs £3,250. Children born in the UK, who are entitled to register as British after ten years’ residence, are required to pay a fee of over £1,000, while those arriving in the UK as young children will have to find visa fees, including the health surcharge, amounting to £8,500 over ten years.

Insofar as these high fees prevent migrants from regularizing their status, they interfere with rights to private life protected by Art 8 ECHR and Art 7 EUCFR.

The cumulative effect of the above measures, in particular the denial of the right to work in lawful employment, the exclusion of migrants from all social security benefits and the exorbitant fees for immigration applications, is to drive many migrants into illegal employment, where they are wholly at the mercy of employers, subject to abuses ranging from sexual harassment to non-payment of wages, and with no legal recourse because of their status, violating rights to access to justice and to an effective remedy for the breach of rights (Arts 2, 7 UDHR, Arts 6, 13 ECHR, Art 47 EUCFR). Non-EU workers without regular status are excluded from access to workplace rights, minimum wage and other protections. Women, who make up a high proportion of these workers, are put at risk of sexual exploitation and abuse in addition to other forms of exploitation, which also directly and indirectly affect children and young people.

(8) Family life: Immigration rules were changed in 2012 so that regular migrants from outside the EU who earn under £18,600 are not entitled to have their spouse or partner join them, and they must earn £22,400 to bring a child as well, and a further £2,400 for each additional child.

The rule change was unnecessary, since migrants seeking to bring in family members were already required to show that they could accommodate and support them without recourse to public funds. It is designed to ensure that poor people cannot have family life in the UK.

The ‘deport first, appeal later’ measures in the 2014 and 2016 Immigration Acts allowed for the removal from the country of migrants who were appealing on the ground that removal would breach their right to respect for their family life, before the appeal was heard.

Many cases have been reported where young children as young as six months old have been separated from their parents by parents’ detention. Bail for Immigration Detainees (BID) has represented 155 parents separated from their children by detention so far in 2018.

The measures interfere with the right to respect for family life, protected by many human rights instruments including UNCRC and Art 8 ECHR. Interference with family life is only permitted in human rights law if it is lawful and necessary in a democratic society for public safety, the prevention of crime, the protection of the rights of others etc.

(9) Policing and detention: In 2012, Operation Nexus was launched, a joint police-immigration enforcement operation which relied on police intelligence rather than findings of guilt to identify ‘high-harm’ individuals for deportation. The following year, the government launched Operation Vaken, an attempt to frighten undocumented migrants into leaving the country, with billboard vans driving around migrant areas telling them to ‘Go Home! Or face arrest’, simultaneously with an aggressive operation involving immigration checks on minority youths at London tube stations.

Enforcement became an important priority in the late 1990s and 2000s. Enforcement officials grew from 120 in 1993 to 7,500 in 2009, when thousands of aggressive raids on ethnic businesses and homes took place. A notorious operation in 2009, which illustrates the relationship between lack of workplace rights and insecure residence rights, involved an ambush on cleaners at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) in London, who had just won the London living wage following a hard campaign. Invited to an early morning meeting, the cleaners found themselves locked in by immigration officials who checked their entitlement to work in the UK and arrested several for deportation. Despite solidarity actions by students, nine were deported. However the cleaners and their supporters continued their campaign for just treatment and in 2017, they won the right to be employed directly by the school, giving them equal pay and conditions with the school’s other workers.

The UK is the only EU member state where indefinite administrative detention of migrants is legal under domestic law, and many immigration detainees have been locked up for several years. There has been a strong campaign, involving many parliamentarians, for a 28-day detention limit. On many occasions, judges have condemned the lengthy detention of vulnerable people, and several times have ruled it inhuman and degrading.Indefinite detention causes mental illness and severe distress, and has resulted in numerous suicides and episodes of self-harm.

The UK was an early privatiser of immigration detention, with Harmondsworth detention centre run by Securicor in the 1970s. Seven of the eight long-term detention centres (now named ‘immigration removal centres’ or IRCs) are privately run. They are exempt from minimum wage legislation, and in 2018, centre managers refused to increase the pay of detainees doing menial work there from £1 to £1.15 per hour.

These measures violate rights to liberty, proclaimed as a peculiarly British fundamental right and value by judges, and also seen as fundamental in the UDHR and the ECHR; to decent conditions of work (see above); and to freedom from inhuman and degrading treatment.

(10) The hostile environment at the borders: As Europe closes its borders to poor migrants and refugees, informal camps have sprung up at the border bottlenecks, where little or no official help has been provided, volunteers seeking to provide help have been criminalised and harsh policing measures have been deployed, including beatings, attacks with dogs, and theft or destruction of belongings. At Calais, where migrants and refugees hoping to cross the Channel to Britain have been arriving since the 1990s, their encampments have been repeatedly destroyed. The big camp known as the ‘jungle’, with makeshift church, school and shops, was bulldozed in October 2016 and police routinely spray sleeping children with tear gas and destroy their tents and sleeping bags, and beat older migrants, while the Calais mayor, seeking to prevent another ‘jungle’ encampment, banned the unauthorised distribution of food and clean water despite diseases such as trench foot developing for lack of clean water. (The ban was overruled by a court which ordered the installation of taps for drinking and washing water.) The UK government contributes to the cost of policing migrants in Calais.

The harsh treatment of those in the encampments and at the borders is inhuman and degrading treatment, contrary to Art 3 ECHR, whose protection is designed to be absolute. Such treatment can never be justified by any policy objective.

3. Specific charges against the UK government (in its own right and as representative of the EU and member states and the global North)

1 Within a work force impoverished and rendered insecure by neoliberal policies, it has ensured that migrant and refugee workers often remain super-exploited, marginalised and deprived of rights by legal and operational measures including:

- Failure (in common with virtually the whole of the global North) to sign or ratify the UN Migrant Workers’ Convention;

- Failure (unlike many other states in the Global North) to ratify the ILO Domestic Workers’ Convention, and the removal of rights and security from domestic workers;

- Legislation imposing employer sanctions for bosses employing undocumented workers, enforced by violent raids on, in particular, small ethnic minority employers, who can be fined up to £20,000 and even imprisoned for employing an undocumented migrant or refugee worker;

- The creation of the criminal offence of illegal working, under the Immigration Act 2016, which allows for the confiscation of workers’ wages;

- The denial and/ or restriction of rights to work for asylum seekers;

- Maintenance of a legal framework which excludes undocumented workers from protection against abuses including non-payment of wages, unfair dismissal and race and sex discrimination, which are particularly rife in the hospitality, leisure, service, agriculture and construction sectors;

- Failure to provide sufficient ongoing funding for the Gangmasters and Labour Abuse Authority (GLAA) to enforce decent conditions of work;

- Failure to provide legal aid in employment-related cases, and the removal of public funding for advice and assistance in these cases;

- Failure to ensure complete separation of enforcement visits by GLAA from immigration enforcement;

- Removal of European Economic Area (EAA) nationals who are destitute and who cannot find work;

- The exemption of immigration removal centres from minimum wage legislation, enabling multinational security companies to profit both from the detention contracts and from the cheap labour of detainees.

2. Meanwhile, the government’s policies with regard to immigration and asylum have fostered racism, Islamophobia and nativism, and have deliberately created a ‘hostile environment’ for non-citizens which involves (in addition to the criminalisationof work) enforced destitution, denial of rights to housing and essential medical treatment, indefinite detention and deportation. These policies violate international human rights obligations to protect rights to life, to dignity, to physical and psychological integrity, to respect for private and family life, to liberty, and to protection from forced labour and from inhuman and degrading treatment. This has been achieved through:

- Increasingly restrictive visa policies which limit legal rights to enter and stay in the UK for work (for non-EEA or third-country nationals) to a small and diminishing number of highly qualified or corporate employees, with extortionate fees for issue and renewal;

- Immigration rules and Home Office policy which treat domestic workers as the property of their employers;

- The provision of no-choice, often squalid asylum accommodation to asylum seekers, who are required to live on an impossibly small weekly allowance;

- Legislation requiring private landlords and agents to check immigration status before renting out accommodation;

- Legislation and policy that denies most refused asylum seekers, and undocumented migrants, any benefits or support, as well as any except emergency NHS hospital care;

- The entrenchment of racialised viewpoints about migrants in the control system to the point that people of colour resident for decades are exposed to the suspicion of having no lawful right to reside, denied essential services, and threatened with enforced removal;

- The removal of legal aid for non-asylum immigration cases;

3. The government, by policies which make it impossible to live without working and simultaneously making work illegal, forces vulnerable people to accept conditions of super-exploitation and total insecurity as the price of remaining in the country, and enables private companies to profit from such super-exploitation.

4. Additionally, while EU free movement law recognises the importance of family unity for EEA nationals who move in order to work, the government’s family reunion rules for non-EEA nationals (whether they are admitted as workers or as refugees) are extremely restrictive and result in long-term separation of families.

5. These policies also work to the detriment of the rights of children, who are exposed to risks of exploitation and abuse when they attempt to migrate in their own right, or to hardship and destitution as a consequence of policies which deny public funds support to family migrants.

6. At the same time, the government, in its own right and as an EU member state, facilitates the making of vast profits by security corporations through contracts for the border security regime, the housing of asylum seekers and for the detention and deportation of migrants, while overlooking or condoning brutality, racism and other human rights violations, criminal offences, fraud and negligence, committed by their agents against migrants and refugees, in fact rewarding them through the continuing award of such contracts.

Questions for the Tribunal

The Tribunal is asked to consider the cumulative effect of all these measures, policies and operations taken together, in creating and maintaining a people without rights within Europe and at its borders.

- To the extent that the Tribunal finds the above violations proved, how to they fit with the general pattern of violations found by the Tribunal in its hearings at Barcelona, Palermo and Paris?

- How does the creation and maintenance of a rightless people sit with the pretensions of Europe to be a cradle of universal human rights and values and with the human rights instruments written, signed and ratified by European states?

- How does the continued tolerance of the suffering of those condemned as rightless affect the rule of law?

- Since the protection of fundamental human rights is designed to embrace both the executive and juridical arms of state, to what extent does the treatment of migrants destroy this bridge between the political and the juridical?

- To what extent can are migrants experimental subjects or guinea-pigs for a broader destruction of the rights of populations under globalisation?

- How do government policies and ministerial statements treating poor migrants and refugees as ‘benefit tourists’, ‘health tourists’, ‘a swarm’, help to exacerbate popular racism and encourage hatred of migrants and racial violence?

- Has the Tribunal found examples of resistance against these measures which can act as models or markers for future action?

[1] Insofar as the ILO Migration for Employment Convention and the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights’ requirements of decent and safe working conditions apply only to workers lawfully on the territory, these instruments themselves unjustifiably and wrongly entrench the exclusion of undocumented migrants from rights recognised as universal.

- END-

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!