Permanent Peoples' Tribunal Hearing

The Human Rights of Migrant and Refugee Peoples

EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT, BRUSSELS

on Tuesday 9thApril from 9.00-13.00

Room ASP 1G2

Panel of judges

Bridget Anderson (UK)

Professor of migration, mobilities and citizenship at Bristol University, Anderson is also Director of Migration Mobilities Bristol (https://migration.blogs.bristol.ac.uk/). She has been Professor of migration and citizenship and research director at COMPAS in Oxford. She has a DPhil in sociology and previous training in philosophy and modern languages. She has explored the tension between labour market flexibilities and citizenship rights, and pioneered an understanding of the functions of immigration in key labour market sectors. She is the author of Us and Them? The Dangerous Politics of Immigration Controls(Oxford University Press, 2013) and Doing the Dirty Work? The Global Politics of Domestic Labour(Zed Books, 2000). She coedited Who Needs Migrant Workers? Labour Shortages, Immigration and Public Policy with Martin Ruhs(Oxford University Press, 2010 and 2012), The Social, Political and Historical Contours of Deportationwith Matthew Gibney and Emanuela Paoletti (Springer, 2013), and Migration and Care Labour: Theory, Policy and Politicswith Isabel Shutes (Palgrave Macmillan, 2014). Anderson has worked closely with migrants’ organisations, trades unions and legal practitioners at local, national and international level. I'm

Perfecto Andrés Ibáñez (Spain)

Magistrate of the Supreme Court of Spain and director of the magazine “Jueces para la Democracia”. He is member of the Permanent Peoples’ Tribunal.

Luciana Castellina (Italy)

Born in Rome in 1929, graduated in law, journalist, deputy of the Chamber of Deputies and the European

Parliament between 1976 and 1999, former vice-president of the Parliamentary Delegation for Central

America and for South America, president of the Culture, and External Economic Relations Committee of the European Parliament. She was vice president of the International League for the Rights of the People,

currently the honorary president of the ARCI, an Italian cultural and social association.

Mireille Fanon Mendes France (France)

President of the Frantz-Fanon Foundation and member of the Working Group of experts for people of African descent of the Human Rights Council of the United Nations

Franco Ippolito (Italy)

President of the Lelio Basso Foundation and former President of the Permanent Peoples’ Tribunal. Section President and previously Secretary-General of the Supreme Court of Cassation. He has been the Secretary-General of the Associazione Nazionale dei Magistrati, the President of Magistratura Democratica, President of the Associazione Italiana Giuristi Democratici, a member of the Consiglio Superiore della Magistratura, and Director-General of the judicial organisation of the Justice ministry. He has written essays and lectures in national and international courses in the field of jurisdictional guarantees and of judicial organisation. He has taken part in numerous international missions in Europe and Latin America (in Argentina, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Ecuador, El Salvador, Nicaragua, Mexico and Peru).

Claire-Marie Lievens (Belgium)

Legal adviser in foreigners and asylum law for the Human Rights League in Belgium (Ligue des Droits Humains).

Luis Moita (Portugal)

He is a Professor of International Relations at the Autonomous University of Lisbon, where he is the Director of the OBSERVARE research centre which publishes an annual report and of the bi-annual scientific publication JANUS.NET, e-journal of International Relations. He directed the Portuguese NGO CIDAC, Amilcar Cabral Information and Documentation Centre, for 15 years. He is a founder member of the Portuguese Council for Refugees. He has cooperated with the Basso Foundation since the 1980s and is a member of the Permanent Peoples’ Tribunal.

Patricia Orejudo (España)

Professor of Private International Law University of the Complutense University of Madrid. Lawyer specialized in Human Rights. PHD in Law. She has taught undergraduate and postgraduate courses, in many other centres in Spain, Europe and Latin America. Member of the state campaign for the closure of Detention Centres for Migrants and the Sol Legal Commission. She has worked in Women's Link Worldwide, a non-profit organization that uses the power of the law to promote and defend the rights of women and girls, as a senior lawyer, and has collaborated with the Spanish Commission for Refugee Aid (CEAR). Investigate issues mainly related to migration from a gender perspective.

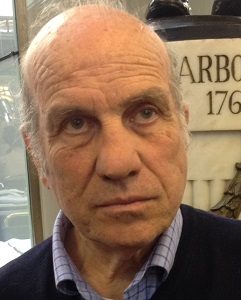

Philippe Texier (France)

President of the Permanent Peoples’ Tribunal, he has been an expert consultant of the French Court of Cassation, from 1997 to 2012. He was also a member of the Committee for Social, Economic and Cultural Rights of the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, which he chaired from 2008 to 2009. He was an independent expert of the Commission for Human Rights in Haiti from 1988 to 1990 and the Director of the United Nations missions in El Salvador, ONUSAL (1991-1992).

Bridget Anderson - Professor of Migration, Mobilities and Citizenship at Bristol University. She formerly held the post of Professor of Migration and Citizenship and Research Director at COMPAS in Oxford. She has a DPhil in Sociology and previous training in Philosophy and Modern Languages. She has explored the tension between labour market flexibilities and citizenship rights, and pioneered an understanding of the functions of immigration in key labour market sectors. She is the author of Us and Them? The Dangerous Politics of Immigration Controls (Oxford University Press, 2013) and Doing the Dirty Work? The Global Politics of Domestic Labour (Zed Books, 2000). She coedited Who Needs Migrant Workers? Labour Shortages, Immigration and Public Policy with Martin Ruhs (Oxford University Press, 2010 and 2012), The Social, Political and Historical Contours of Deportation with Matthew Gibney and Emanuela Paoletti (Springer, 2013), and Migration and Care Labour: Theory, Policy and Politics with Isabel Shutes (Palgrave Macmillan, 2014). Bridget Anderson has worked closely with migrants’ organisations, trades unions and legal practitioners at local, national and international level.

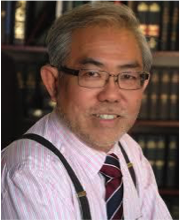

Bridget Anderson - Professor of Migration, Mobilities and Citizenship at Bristol University. She formerly held the post of Professor of Migration and Citizenship and Research Director at COMPAS in Oxford. She has a DPhil in Sociology and previous training in Philosophy and Modern Languages. She has explored the tension between labour market flexibilities and citizenship rights, and pioneered an understanding of the functions of immigration in key labour market sectors. She is the author of Us and Them? The Dangerous Politics of Immigration Controls (Oxford University Press, 2013) and Doing the Dirty Work? The Global Politics of Domestic Labour (Zed Books, 2000). She coedited Who Needs Migrant Workers? Labour Shortages, Immigration and Public Policy with Martin Ruhs (Oxford University Press, 2010 and 2012), The Social, Political and Historical Contours of Deportation with Matthew Gibney and Emanuela Paoletti (Springer, 2013), and Migration and Care Labour: Theory, Policy and Politics with Isabel Shutes (Palgrave Macmillan, 2014). Bridget Anderson has worked closely with migrants’ organisations, trades unions and legal practitioners at local, national and international level. Wah-Piow Tan - A Balliol educated human rights solicitor in London representing Chinese migrants in the UK since 180s. A former political prisoner and exile from Singapore, Wah-Piow is well known since his youth as a student leader, activist, writer and public speaker advocating democratic reforms in Singapore. Most recently, in August 2018, he enjoyed unprecedented extensive media coverage following his 80 minutes discussion with the new Malaysian Prime Minister on the subject of expanding the democratic space in Southeast Asia. In 1980, Wah-Piow attended the Permanent People’s Tribunal (PPT) hearing on The Philippines in Antwerp as an observer.

Wah-Piow Tan - A Balliol educated human rights solicitor in London representing Chinese migrants in the UK since 180s. A former political prisoner and exile from Singapore, Wah-Piow is well known since his youth as a student leader, activist, writer and public speaker advocating democratic reforms in Singapore. Most recently, in August 2018, he enjoyed unprecedented extensive media coverage following his 80 minutes discussion with the new Malaysian Prime Minister on the subject of expanding the democratic space in Southeast Asia. In 1980, Wah-Piow attended the Permanent People’s Tribunal (PPT) hearing on The Philippines in Antwerp as an observer. Maureen Byrne is a Councillor. She is a retired full time Equality Officer in Unite the Union. She has been on the Employment Tribunal panel for 30 years. Currently she is Employment Law adviser for the Stansted Airport Branch. Maureen is chairperson for the Bury St Edmund’s Women’s Aid Refuge and Local Association for Mental and Physical Handicapped Charity, a group supporting young people with special needs. She is the Town Council Chairperson of the Personnel Committee.

Maureen Byrne is a Councillor. She is a retired full time Equality Officer in Unite the Union. She has been on the Employment Tribunal panel for 30 years. Currently she is Employment Law adviser for the Stansted Airport Branch. Maureen is chairperson for the Bury St Edmund’s Women’s Aid Refuge and Local Association for Mental and Physical Handicapped Charity, a group supporting young people with special needs. She is the Town Council Chairperson of the Personnel Committee. Dr Eddie Bruce Jones AB (Harvard); MA (Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin); JD (Columbia); LLM in Public International Law (KCL is currently acting dean and Lecturer in Law at

Dr Eddie Bruce Jones AB (Harvard); MA (Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin); JD (Columbia); LLM in Public International Law (KCL is currently acting dean and Lecturer in Law at  Leah Bassel - is a member of Haringey Welcome, a campaign group working for fairness, dignity and respect for migrants and refugees in the London borough of Haringey. Leah researches the political sociology of migration, intersectionality and citizenship as Professor of Sociology at the University of Roehampton. Her books include Refugee Women: Beyond Gender versus Culture (Routledge, 2012), The Politics of Listening: Possibilities and Challenges for Democratic Life (Palgrave, 2017), and Minority Women and Austerity: Survival and Resistance in France and Britain co-authored with Akwugo Emejulu (Policy Press 2017). She is currently co-Principal Investigator, with Akwugo Emejulu, of the Open Society-funded project Women of Colour Resist and has also led projects funded by the Economic and Social Research Council and the British Academy. Before pursuing an academic career, Leah was an emergency outreach worker in Paris where she provided humanitarian assistance to asylum seekers and created a circus camp project for refugee youth. She holds a DPhil from the Refugee Studies Centre/Nuffield College, University of Oxford and a BA and MA from McGill University, Canada.

Leah Bassel - is a member of Haringey Welcome, a campaign group working for fairness, dignity and respect for migrants and refugees in the London borough of Haringey. Leah researches the political sociology of migration, intersectionality and citizenship as Professor of Sociology at the University of Roehampton. Her books include Refugee Women: Beyond Gender versus Culture (Routledge, 2012), The Politics of Listening: Possibilities and Challenges for Democratic Life (Palgrave, 2017), and Minority Women and Austerity: Survival and Resistance in France and Britain co-authored with Akwugo Emejulu (Policy Press 2017). She is currently co-Principal Investigator, with Akwugo Emejulu, of the Open Society-funded project Women of Colour Resist and has also led projects funded by the Economic and Social Research Council and the British Academy. Before pursuing an academic career, Leah was an emergency outreach worker in Paris where she provided humanitarian assistance to asylum seekers and created a circus camp project for refugee youth. She holds a DPhil from the Refugee Studies Centre/Nuffield College, University of Oxford and a BA and MA from McGill University, Canada.  Enrico Pugliese - is Professor of sociology of work, (Emeritus) at Sapienza- University of Rome, faculty member of the Graduate school in applied sociology, University of Rome La Sapienza. He is also research associate at Irpps (Istituto di ricerche sulla popolazione e le politiche sociali), National research council, Rome. He has been Professor of Sociology of work at the University of Napoles "Federico II" where he served as chairman of the department of sociology and then as dean of the faculty of sociology. He has been visiting professor in several European and American Universities. He has been also meember of the National commission of inquiry on work at the Consiglio nazionale dell’economia e del lavoro, chairman of the Commission for drafting the immigration law of the Regione Campania. He has also been member of the advisory Commission of the City Mayor of Napoli for immigration policy. His main research interests include: international migration, Italian migration in Europe, third world immigration in Italy, migration policies, labour market with special reference to precarious employment and unemployment. His recent publications on migration include: Quelli che se ne vanno (Those who leave), Il mulino 2018, and International Migrations and the Mediterranean in Andreotti, Benassi, Kazepov (eds) Western Capitalism in transition, Manchester University Press 2018.

Enrico Pugliese - is Professor of sociology of work, (Emeritus) at Sapienza- University of Rome, faculty member of the Graduate school in applied sociology, University of Rome La Sapienza. He is also research associate at Irpps (Istituto di ricerche sulla popolazione e le politiche sociali), National research council, Rome. He has been Professor of Sociology of work at the University of Napoles "Federico II" where he served as chairman of the department of sociology and then as dean of the faculty of sociology. He has been visiting professor in several European and American Universities. He has been also meember of the National commission of inquiry on work at the Consiglio nazionale dell’economia e del lavoro, chairman of the Commission for drafting the immigration law of the Regione Campania. He has also been member of the advisory Commission of the City Mayor of Napoli for immigration policy. His main research interests include: international migration, Italian migration in Europe, third world immigration in Italy, migration policies, labour market with special reference to precarious employment and unemployment. His recent publications on migration include: Quelli che se ne vanno (Those who leave), Il mulino 2018, and International Migrations and the Mediterranean in Andreotti, Benassi, Kazepov (eds) Western Capitalism in transition, Manchester University Press 2018. This November the hostile environment will be out on trial in front of a panel of expert jurors.

This November the hostile environment will be out on trial in front of a panel of expert jurors.

Overworked, underpaid and undervalued, London hotel workers are speaking out.

Overworked, underpaid and undervalued, London hotel workers are speaking out.